The Broad Street Water Pump, Soho, London

The Broad Street Water Pump, Soho, London

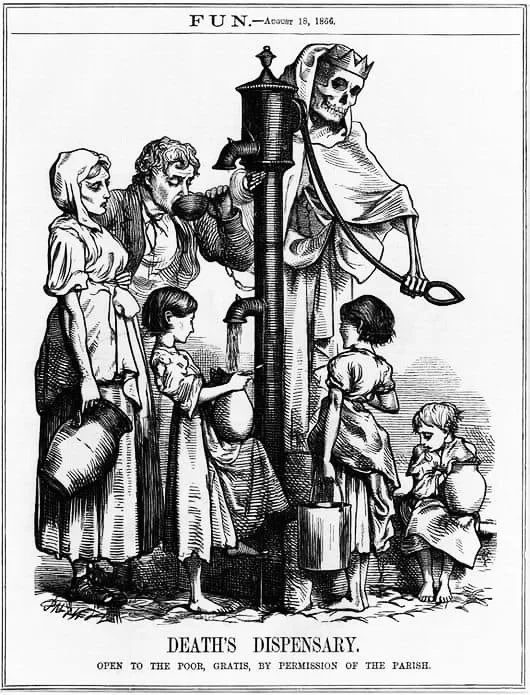

London in the Time of Cholera

One of the earliest outbreaks of Cholera was recorded in India in 1817, and from the Ganges, it quickly spread to the rest of the world via global trade routes and military movement. Eventually, it arrived in England, with Britain seeing its first major Cholera outbreak in the year 1831. The disease quickly spread throughout the country, resulting in an estimated 50,000 deaths. London was especially hard hit thanks to its rapidly expanding population and poor sanitation infrastructure at the time. Doctors didn't know where the disease came from, nor, importantly, how to treat it. They believed in the theory of miasma, a popular idea that disease was spread through bad air and horrible smells, rather than through dirty water and poor sanitation.

What we now know is that Cholera is caused by a type of bacteria called Vibrio cholerae, which attacks the small intestine and causes what is described as “rice-water stools.” Those affected can lose up to 20 litres of fluid a day, which, back in Victorian times, was often deadly, especially for the very young and old. Another important fact that we know about Cholera today is that the disease is not transmitted via bad smells, but instead is spread via the faecal–oral route, or what my microbiology professor described as: ‘from the anus of one to the mouth of another’. This transmission was usually through food and water contaminated with human waste. And so, without any proper sanitation in place, or indeed, even the concept of how the disease spread, the people of Britain saw outbreak after outbreak, death after death.

Today, thankfully, Cholera is largely preventable through proper sanitation and clean water infrastructure and is rarely seen in the UK unless brought back by an unlucky traveller returning from abroad. Cholera is both easily treatable and avoidable through an effective vaccine for those travelling to areas at risk. But despite all of this, the disease continues to claim an estimated 95,000 lives each year, predominantly in regions of the developing world where sanitation remains poor, and access to medical care is limited.

The Birth of Modern Public Health

London’s Cholera epidemics of the early 1800s led the city to try to contain the situation. The lawyer Edwin Chadwick was given the job of investigating the city’s sanitation practices following the first cholera outbreak. At a time when human waste and animal carcasses were commonly left outside homes, littering the streets, Chadwick proposed that the waste be diverted into the River Thames in the hopes that with the riddance of the foul air and bad smells, the city would be rid of cholera once and for all. While these measures greatly improved the condition of the streets, they proved disastrous for the city’s water supply, as the Thames was also the primary source of drinking water for Londoners.

But luckily for the people of London, as the city faced its third cholera outbreak, the physician John Snow came up with a novel theory and, in 1849, published On the Mode of Communication of Cholera, in which he argued that the disease was not transmitted through bad air and smells as previously thought, but through contaminated water instead. Snow tested this theory by mapping cholera cases in the area surrounding Broad Street, where his medical practice was located. And what he found was that the cases all clustered around a single, likely source: the Broad Street water pump. Following this discovery, Snow ordered the removal of the pump handle, after which cholera deaths in the area sharply declined, thus ending the outbreak.

Although Snow’s theory was largely dismissed by the medical establishment at the time, London’s Great Stink of 1858 helped prove him right. Hot weather combined with vast amounts of raw sewage in the River Thames caused the city and its inhabitants to suffer unbearable smells. This assault on the senses led to the construction of London’s modern sewage system, which in turn, resulted in significant improvements in public health and communicable diseases. Thus, finally proving John Snow’s water pump theory correct and establishing the link between cholera and contaminated water supplies.

Soho, London

Top Tips

Free to visit, the infamous water pump can be found on Broad Street in the heart of Soho, positioned amongst busy cafés and restaurants. Countless people pass it each day, stepping around the pump without a second glance, unaware that modern public health owes much to the events that unfolded at this very spot.

The pump visible today is a replica, installed on the site of the original pump. It also serves as the location for the annual Pump Handle Lecture organised by the John Snow Society. Following the lecture, the pump handle is ceremonially attached and removed, after which attendees traditionally gather at the nearby John Snow pub.